With state and local energy codes marching unflinchingly towards a zero-carbon future, projects seeking to show deep sustainability commitments by going beyond energy code requirements are faced with fewer compelling design options. This may be especially true for large scale projects or multi-building developments, many of which have unique constraints on space and more limited system options. Efficiency focused electric district energy systems, or low-carbon energy districts, have been seeing more widespread adoption in the Pacific Northwest and can help fill this unique niche.

What are low-carbon energy districts?

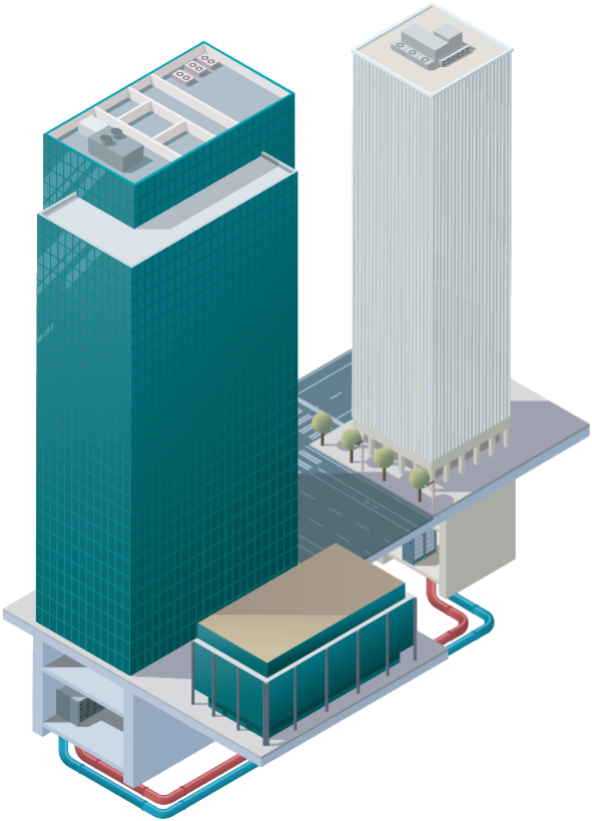

|

| Image courtesy of McKinstry |

Low-carbon energy districts are communities of buildings connected via common energy infrastructure and systems, designed and operated together with a common goal of reducing carbon emissions and utility energy usage. They include many or all of the following attributes:

- shared energy

- zero carbon commitments

- common digital infrastructure

- utility and building owner partnerships

- engaged occupant community

They seek to marry abundance in one building to another with a complementary scarcity. An example might be a warehouse with a large roof available for solar photovoltaics adjacent to a mid-rise office building with scarce roof space. Another example might be a data center with ample available waste heat it normally rejects to the environment and adjacent commercial buildings seeking a source of efficient heating.

Low-carbon energy districts are part of a larger district-focused certification program called EcoDistricts, which expand beyond energy and carbon to include community goals such as social justice, equity, health and wellbeing, and other important priorities.

|

|

| Image courtesy of McKinstry |

Benefits of low-carbon energy districts

Low-carbon energy districts in our heating dominated region are often formed around the nucleus of a thermal heat source and are designed to distribute that energy to connected buildings seeking heat. Data centers, municipal sewers, and large ground heat wells are all good candidates to use as heat sources. Using these heat sources enable district connected buildings to heat and cool using two to three times less energy than if they were to operate standing alone. This can drive significant utility savings that can be captured by the connected buildings in the energy district.

Energy districts accelerate the process of electrification, helping respond to corporate carbon reduction goals. They also enable the connected community of buildings to monitor and respond to their collective energy needs, increasing resilience and providing more stable operating conditions for the electricity grid. These increasingly valuable attributes are often rewarded with grants and incentives from utilities and municipalities as they anticipate a more volatile energy future.

Low-carbon energy districts can leverage economies of scale to reduce the costs of deploying energy systems and technologies that may have unattractive cost premiums in most individual buildings.

Energy districts are challenging to design and implement, but more often the biggest hurdles are addressing the complexity of contract structures and additional permitting. Tackling them early is key.

Challenges of implementation

Energy is a valuable resource, and it must be appropriately valued and tracked. Heat that a building would normally reject has no value until a neighboring building can be identified that has a concurrent heat need. Valuing that energy is less than straightforward. Aligning the interests of all potential buildings or partners that connect to an energy district requires unique relationships of trust, plain-language communication, and technical expertise that is likely to require a specialized team. Education is key - the resulting agreements may be foreign to many in the development community.

Setting up an energy district that supplies multiple buildings under different ownership creates a utility, which comes with its own set of specialized regulations. Permits to tap heat resources may require additional environmental review; local, county, and/or state permitting and approval; and other processes that demand additional time, commitments, and influence. Simply having infrastructure cross public right of way triggers additional permitting and fees.

The value that that low-carbon energy districts can drive is significant but pursuing them requires all-in commitment. Be prepared for a long, complex process.

|

| Image courtesy of the UN District Energy in Cities Initiative |

Examples of low-carbon energy districts

Thankfully, we don’t have to look too far for low-carbon energy districts to inspire us. Use the links below as a jumping off point to explore a few projects making a difference in our region.

- The Amazon campus in the Denny Regrade features an innovative low-carbon energy district that re-uses waste heat from the Westin data center across the street to heat the office towers.

- The False Creek Neighborhood in Vancouver, BC has a large sewage waste heat recovery system that provides heating for over five million square feet of development.

- The South Landing Eco-District in Spokane features both solar PV arrays and a state-of-the art central plant delivering heating and cooling to community buildings, built and planned.

The above North America centric examples are just a start. Check out the UN District Energy in Cities Initiative to look at the amazing things folks are doing in cities across the world!

This blog was written by Michael Hedrick (McKinstry) as part of an ongoing series by our Sustainable Development committee called "Sustainability Mindset." For more information about the Sustainable Development committee, click here.